Summary of Conflicts

|

1655 to 1660 (links to map of Poland) The Bloody 'Deluge' Before the Swedish invasion the numbers of infantry and dragoons had fallen to a few thousand and most of the regular army was in the east fighting the Muscovite-Cossack alliance. In an attempt to halt the Swedish attack a call-up of 'lanowa' (fief) infantry was made and applied to all Polish provinces. It consisted the raising of one peasant infantryman (with musket, sabre, axe and uniform in his district colour, food for a year and a wagon per five men) per lan of land (approx. 17 hectares) and was extended, with modifications, to towns. These excellent beginnings were ruined at the shameful capitulation of the fortified Polish army, of mainly noble levy and "lanowa" infantry, at Ujscie (25 July 1655) by the treasonous Krzysztof Opalinski. However only 800 of the 13,000 noble cavalry surrendered, the remainder were surprised by Opalinski's treachery and escaped to fight another day. In Lithuania Janusz Radziwill, Hetman of the Lithuanian army, seeing the Commonwealth falling apart attempted to gain personally from the situation and on 17th August offered Lithuania to the Swedes. Defeats combined, at Grodek (29 September 1655) Muscovite-Cossack forces defeated Potocki's division and three days later Polish forces were defeated by the Swedes at Wojnicz (3rd October 1655). On 17th October with no hope of relief, Czarniecki surrendered Krakow. So by the end of 1655 almost all of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was occupied by either Sweden, Muscovy or the Cossacks. Of the main towns only Gdansk and Lvov held out. The remains of the Polish army entered Swedish service. However at the time of greatest crisis, when it looked like Poland would be lost, a national revival began. Charles discovered that holding onto Poland would be a more difficult task than its capture. He attempted to win over the nobility, however his army ravaged and pillaged the land, massacring the Catholic population and anti-Swedish riots appeared in November, while in West Poland a partisan war began. In the south the highlanders revolted while in Podlesie most of the Lithuanian troops left the traitor Radziwill. Then a general uprising was triggered when the Swedes attempted to take the Holy Shrine at Jasno Gora Monastery near Czestochowa. Jan Kazimierz returned from temporary exile and the Poles began to rally. Their only ally was the Khan, although Muscovy, concerned at Sweden's rise, promised a truce. So with their rear relatively secure the Poles used all their forces on the Swedish King and his veterans.

The losses during the Cossack wars and the early part of the Swedish invasion meant the army was much more improvised in character, its training and equipment was inferior and though it often attacked with passionate fury, it was weak in defence and easily panicked and dispersed. The Swedes had an immense firepower superiority and had a definite advantage in battle, their cavalry had improved (compared to the 1620's) and was comparable in quality to the Polish cavalry, although the small numbers of hussars remained very much superior. Charles moved with the majority of his army for Lvov, but his advance became a succession of disasters, with Czarniecki harrying the Swedes at every opportunity. Charles was surrounded by Polish Lithuanian forces at the fork of the rivers Vistula and San. Frederick Baden's force of 4,500 moved to assist Charles, but was ordered to return to Warsaw due to the difficulty of moving through partisan territory. After a forced march Polish forces caught up with them at Warka on 7th April 1656 and destroyed Baden's force. Only a few survivors managed to reach Warsaw, the rest were cut down amongst the forests by local peasants. By a skillful feint Charles evaded the Polish trap and moved on to Warsaw. By June 1656 Southern Poland,

bar Krakow, was cleared and in July the Poles met the Swedish-Brandenburg

forces in the three day battle of Warsaw

(29-31 July 1656). The tactics which finally succeeded against the Swedes, were ones similar to Koniecpolski's tactics against the Swedes in Prussia (1626-29) although on a much larger scale. This campaign of harassment was led by the brilliant cavalry commander Stefan Czarniecki, ably supported by Hetman Lubomirski. Direct battles were avoided, and methods depended on using mobility to the full, with the main army being strengthened by the local Population. Tactics like these were necessary because of the cavalry character of the army and persisted until around 1658. By early in 1656 the hungry Swedes were forced to retreat from Little Poland into Mazovia and General Czarniecki sought every opportunity to destroy isolated units, pushing to its limits the art of maximum mobility, using forced marches and night manoeuvres to force the enemy to fight. In Lithuania Polish-Tartar forces combined in a coordinated attack on a Swedish-Brandenburg army and crushed them at Prostki (8 October 1656).

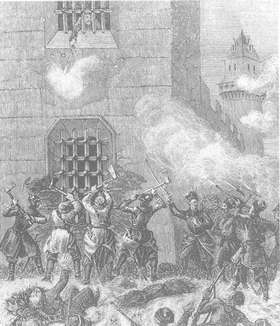

On 25 July 1657, with assistance from the Emperor, Krakow was recaptured and almost the whole country was free. All that was left was to evict the Swedes from their Pomeranian strongholds. For this the army would need to be reorganised to provide a significant infantry arm, and the Sejm was organised. The first target was Torun which was finally taken with heavy losses in a wholesale attack on the night of 16/17 November 1658. In 1660 peace was signed at Oliwa, where the pre-1655 position was reaffirmed. The war had brought little profit to Sweden but had lost Poland East Prussia (to Brandenburg) and plunged her into economic ruin. Poland's final success against the Swedes was not translated into a more advantageous agreement due to the renewal of troubles in the east. |

|

![]()

Charles

X Gustavus of Sweden seeing the trouble in Poland and Lithuania

and ignoring the treaty of Stumdorf invaded west Poland in July

1655 and so began the period known in Polish history as the Deluge.

Charles

X Gustavus of Sweden seeing the trouble in Poland and Lithuania

and ignoring the treaty of Stumdorf invaded west Poland in July

1655 and so began the period known in Polish history as the Deluge. In

August new Swedish forces arrived and together they marched on Warsaw.

At

In

August new Swedish forces arrived and together they marched on Warsaw.

At  The

Hetman universal order of December 1655 ordered the mobilisation

of the noble levy, one cavalryman per five 'lan' and one infantryman

per ten 'dymy' (homesteads), but because of shortages in arms and

equipment in 1656 a call-up of the entire population "even

with scythes and axes" took place.

The

Hetman universal order of December 1655 ordered the mobilisation

of the noble levy, one cavalryman per five 'lan' and one infantryman

per ten 'dymy' (homesteads), but because of shortages in arms and

equipment in 1656 a call-up of the entire population "even

with scythes and axes" took place. The

36,000 strong Polish army, including 4,000 infantry and 1,000 hussars,

met an enemy force of 18,000. During the battle six standards of

hussars charged the Swedish left wing, composed of six infantry

brigades in two lines, and smashed the Swedish first line and broke

into the second line. Only the high discipline and training of the

Swedes stopped an instant rout. At the same time Tartars hit the

Swedes from the rear, but all was in vain, the rest of the army

did nothing and the unsupported hussars were forced to return, with

16% losses. A decisive defeat could have been inflicted but for

the ill-discipline of the rest of the army, and instead the Poles

were forced to retreat. Though the Poles were defeated, the Swedes

were unable to pursue. Polish troops invaded Brandenburg in revenge

for the Elector's treason and Tartar forces plundered East Prussia.

The

36,000 strong Polish army, including 4,000 infantry and 1,000 hussars,

met an enemy force of 18,000. During the battle six standards of

hussars charged the Swedish left wing, composed of six infantry

brigades in two lines, and smashed the Swedish first line and broke

into the second line. Only the high discipline and training of the

Swedes stopped an instant rout. At the same time Tartars hit the

Swedes from the rear, but all was in vain, the rest of the army

did nothing and the unsupported hussars were forced to return, with

16% losses. A decisive defeat could have been inflicted but for

the ill-discipline of the rest of the army, and instead the Poles

were forced to retreat. Though the Poles were defeated, the Swedes

were unable to pursue. Polish troops invaded Brandenburg in revenge

for the Elector's treason and Tartar forces plundered East Prussia.

Charles

saw his only hope was to arrange, with Chmielniecki and George Rakoczy

of Transylvania, the partition of Poland. In January 1657 some 40,000

Cossack-Transylvanian forces crossed the Carpathians and Charles

left Torun marching South with some 7,000 cavalry and dragoons to

meet them. The Poles, outnumbered avoided battle. In the Summer

news reached Charles of war with Denmark and he returned home, accompanying

Rakoczy as far as Warsaw. Rakoczy soon left the city on news of

Lubomirski's forces devastating Transylvania. At Magierow (17 July

1657) he was defeated and seven days later he was surrounded by

the Poles and forced to surrender. He agreed to the payment of large

war duties and on his journey home the Tartars destroyed his forces

at

Charles

saw his only hope was to arrange, with Chmielniecki and George Rakoczy

of Transylvania, the partition of Poland. In January 1657 some 40,000

Cossack-Transylvanian forces crossed the Carpathians and Charles

left Torun marching South with some 7,000 cavalry and dragoons to

meet them. The Poles, outnumbered avoided battle. In the Summer

news reached Charles of war with Denmark and he returned home, accompanying

Rakoczy as far as Warsaw. Rakoczy soon left the city on news of

Lubomirski's forces devastating Transylvania. At Magierow (17 July

1657) he was defeated and seven days later he was surrounded by

the Poles and forced to surrender. He agreed to the payment of large

war duties and on his journey home the Tartars destroyed his forces

at  A

Polish-Danish alliance started with a Danish attack by land and

sea at Sweden, though the Danes were soon defeated. In the Autumn

of 1658 Polish, Austrian and Brandenburg troops led by Czarniecki

set off to assist Denmark. Here Czarniecki led his cavalry in a

famous swim across sea straits to attack the Swedes at the island

of Alsen (14 December 1658) and on the 25th his dismounted forces

captured Koldynge castle. While town by town the Swedes were evicted

from Prussia. In Pomerania 1659 a two pronged offensive by the Swedes

was crushed and the Poles went on the attack with some 54,000 regular

forces, recapturing many Swedish occupied towns.

A

Polish-Danish alliance started with a Danish attack by land and

sea at Sweden, though the Danes were soon defeated. In the Autumn

of 1658 Polish, Austrian and Brandenburg troops led by Czarniecki

set off to assist Denmark. Here Czarniecki led his cavalry in a

famous swim across sea straits to attack the Swedes at the island

of Alsen (14 December 1658) and on the 25th his dismounted forces

captured Koldynge castle. While town by town the Swedes were evicted

from Prussia. In Pomerania 1659 a two pronged offensive by the Swedes

was crushed and the Poles went on the attack with some 54,000 regular

forces, recapturing many Swedish occupied towns.